Wenceslao Amezcua

In 2023, at the Faculty of Communication at MSVU, we lost one of our most remarkable professors, Wade Kenny. He was a unique individual—sometimes deep and profound, yet at other times light-hearted, funny, and entertaining. Without a doubt, he was a brilliant man.

His passing was both surprising and deeply saddening, but remembering his legacy at the University will always be a source of joy and thought-provoking reflection. We will all miss him greatly.

I had the privilege of being his student in the Master’s program in Public Relations. I witnessed firsthand his extensive knowledge in communication, sociology, and popular culture, as well as his kindness and respect for his role as a professor.

In light of this, I would like to share with you, my dear colleagues, the final paper I wrote for his course. It explores a topic we both cherished: the world of wrestling and its spectacle of exaggeration and excess. I hope you enjoy it.

World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) is the largest wrestling promoter in the world. Its history can be traced back to 1952 when Jess McMahon founded the Capital Wrestling Corporation (CWC). After undergoing several name changes, the company adopted the name WWE in 1999. Throughout its history, the brand has always remained within the McMahon family, and it has been traded on the New York Stock Exchange as WWE ever since (Street, 2017). According to its official website, WWE reported a 10% increase in revenue to $801.0 million in 2017, marking the highest in the company’s history (Financials, n.d.). Indeed, WWE operates within the amusement industry and not in the sport business. Not surprisingly, WWE is a spectacle of excess, much like successful freak shows that have become rare scientific spectacles (Brigham, 2007).

WWE is not only an example of popular culture but also a powerful media product capable of creating and reinforcing stereotypes and archetypes. Analyzing the freak shows presented in WWE using a structural method is relevant for understanding a significant aspect of our spectacle-driven civilization, where everyone is invited as a spectator and participants range from athletes to freaks to even potential Presidents of the United States.

I will analyze the inclusion of sideshows in WWE as symbols of this spectacle. The analysis will be conducted through the theoretical lens proposed by Roland Barthes in his essay “The World of Wrestling.” One of the key parallels between the freak show and wrestling, viewed through structural principles, is the use of wrestling as a spectacle based on immediate pantomime—gestures aimed at appearing authentic. Throughout this process, many clichés emerge: aesthetics, suffering, justice, fear, pride, and more. In WWE, much like in the freak show, pantomime is animated with anecdotes, discourses, and stories. Here, one encounters the good, the bad, the ugly, the hero, the villain, and the powerful. Extreme characterization, simulated brutality, public humiliation, absurd storylines, cruelty, and comedy—all are ingredients shared by pro-wrestling and freak shows alike.

Another important point regarding these spectacles as profitable business, as Steinberg (2012) points out, is that within this industry there are both heroes and villains, and even more unscrupulous characters in suits. Wrestlers, entertainers, and promoters alike have chosen to build their lives around this profession. The performers and fighters are individuals seeking employment, not just victory, often for their very survival. Like anyone else, their careers and pride are not assured. WWE understands the pulse of its American male audience, craving excess, and provides shows that tap into conflicts they uniquely comprehend.

Definitions of Freaks

Human curiosities, rarities, sideshows, oddities, biological anomalies, misfits, natural malformations, strange beings, abnormalities, phenomena, acts of God, monsters, and very special people… There are many terms to describe “Freaks.” I will use the word “freaks” as it has been commonly used in several fields.

According to the British Library, the term “freak” has been used to describe people born with ‘abnormal’ features or those who can perform extraordinary physical acts by contorting or misshaping their bodies (Victorian freak shows, p. 1). Similarly, the Encyclopedia Britannica describes a Freak Show as an exhibition of exotic or deformed animals as well as humans considered in some way abnormal or outside broadly accepted norms (Chemers, n.d., p. 1).

Regarding the origin of the word, the same Encyclopedia says that it descends from the Old English word “frician,” meaning “to dance.” “Freking” signified sudden movement or capricious behavior. Based on this, naturalists attempted to find specific categories for all life forms that did not match a perceived species average; they were often referred to as freaks of Nature. In general, then, the definitions of freaks have two keywords that can help build different definitions: abnormal and outside. In both cases, there is the idea of people outside the social expectations of body, shape, thinking, or acting.

The Construction of a Freak

“A freak, according to Bogdan (1988), is not a quality that belongs to a person; rather, it is something that we create: a perspective, a set of practices, a social construction. In other words, a freak is a frame of mind, a set of practices, a way of thinking about and presenting people. The social construction — the manufacture of freaks — is the main attraction (p. 4).

We can divide people into those born as freaks (with physical disabilities), those made into freaks (through alteration of the body), or those who act as freaks (conscientious behavior). In this sense, the presentation of freaks in professional wrestling encompasses all three types: for example, those born with special conditions (e.g., midgets); those transformed into freaks (e.g., extreme bodybuilding); and those who act as freaks (such as those who pretend to bury their rivals).

On the other hand, Leslie Fiedler, in her famous book ‘Freaks’ (1978), goes beyond physical appearance and considers freaks from a psychoanalytic perspective. She describes how humans have a deep, psychic fear of people with specific abnormalities. For example, dwarfs represent our fear that we will never grow up. In wrestling, short persons form one of the largest groups of freaks, alongside giants. However, unlike giants, dwarfs are usually involved in opening acts and comical shows, far from serious battles. One event where dwarfs were portrayed as an absolute comedic spectacle was the “Capture the Midget” presentation, where two professional wrestlers had to hunt down and apprehend a little person. Throughout the evening show, these wrestlers ran all over the arena with nets and bags in pursuit of the dwarf. By the end of the night, the dwarf made his way to the stage, escaping into the crowd until he reached the TV announcer. He then sat on the lap of one of the presenters, who declared him the winner of the “Capture the Midget” contest.

On the other hand, Leslie Fiedler, in her famous book ‘Freaks’ (1978), goes beyond physical appearance and considers freaks from a psychoanalytic perspective. She describes how humans have a deep, psychic fear of people with specific abnormalities. For example, dwarfs represent our fear that we will never grow up. In wrestling, short persons form one of the largest groups of freaks, alongside giants. However, unlike giants, dwarfs are usually involved in opening acts and comical shows, far from serious battles. One event where dwarfs were portrayed as an absolute comedic spectacle was the “Capture the Midget” presentation, where two professional wrestlers had to hunt down and apprehend a little person. Throughout the evening show, these wrestlers ran all over the arena with nets and bags in pursuit of the dwarf. By the end of the night, the dwarf made his way to the stage, escaping into the crowd until he reached the TV announcer. He then sat on the lap of one of the presenters, who declared him the winner of the “Capture the Midget” contest.

Continuing with psychological terms, Fielder suggests that when freaks project aspects of the self, they provoke fear and revulsion. Moreover, when we encounter “Freaks, monsters, or mutilés,” as described in French thanatology, we cross a boundary in our imagination that, in childhood, we could never be certain existed, entering a realm where what distinguishes us as normal on one side, and freaks on the other, becomes unclear (p. 28).

Additionally, with the emergence of the freak show, it has become a metaphor for estrangement, alienation, and marginality; the darker aspects of the human experience. The construction of the alienation of a human being into an attractive freak is seen as crude, offensive, and ultimately exploitative and despicable, a form of disability pornography (p. 2).

Representation of Freaks as a Spectacle

Freaks have been displayed in various forms since time immemorial. However, as a profitable spectacle, as explained by the British Library, they appeared in travelling fairs, circuses, and taverns in England since the 1600s. These included giants, dwarves, obese individuals, the very thin, conjoined twins, and even people from exotic lands. Nevertheless, the representation of freaks has permeated popular culture, literature, and cinema (p. 3).

“Freak-show performers (otherwise known as ‘human curiosities’) were first presented in America as early as 1738, though they appeared more frequently in the context of scientific lectures rather than theatrical performances. During the mid-19th century, many individuals gained significant legitimacy, respectability, and profitability by performing their acts within the context of this new form of American entertainment. By 1860, human curiosities had become one of the primary attractions for American audiences.

Several factors contributed to the decline of the freak show in the 20th century. For example, the medical model of disability changed the narrative from one of wonder to one of pathology, and there was an increase in other forms of human attractions available to the general public. Today, the relationship between freak-show performance and disability remains complex because not all performers were individuals with disabilities. In the 21st century, the freak show has persisted in the United States and elsewhere as part of the avant-garde underground circus movement (Chemers, n.d.).

According to Whittington-Walsh (2010), at the turn of the nineteenth century, the Protestant ethic combined with Victorian morality helped to turn audiences away from freak shows. One of the main arguments to stop them was because they were perceived as exploitative to the performers. Nonetheless, closing the freak shows isolated the performers socially and economically. However, images of people with disabilities as entertainment did not disappear. The freak show lost its power and impact “since the world of science and medicine took over the freak shows and the mainstream film industry created replacement images, performers with disabilities have virtually become invisible, while images of disability have been appropriated into negative stereotypes” (p. 705).

On the other hand, Bogdan (1988) states that freak shows disappeared because the performers had become curiosities of pathology and the scientific world was taking over as chief exhibitors, stigmatizing the performers with links to illness and deviance (pp. 65–66). This stigma was such that visibility produced fear and repulsion and led to segregation and invisibility.

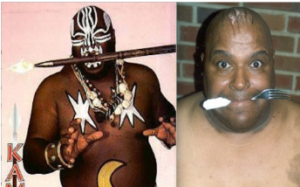

In this sense, Bogdan distinguished two different styles of presenting people with disabilities in freak shows. One is the exotic mode of presentation, where the performer was presented in a way that would “appeal to the spectators’ interest in the culturally strange, the primitive, the bestial, the exotic.” Examples of this type in wrestling are the Great Kamala from Uganda or Abdullah the Butcher, the Madman from Sudan, who carved a bloody swath with a fork through his opponents. Both had the image of African savages and were over 400-pound semi-naked men.

In this sense, Bogdan distinguished two different styles of presenting people with disabilities in freak shows. One is the exotic mode of presentation, where the performer was presented in a way that would “appeal to the spectators’ interest in the culturally strange, the primitive, the bestial, the exotic.” Examples of this type in wrestling are the Great Kamala from Uganda or Abdullah the Butcher, the Madman from Sudan, who carved a bloody swath with a fork through his opponents. Both had the image of African savages and were over 400-pound semi-naked men.

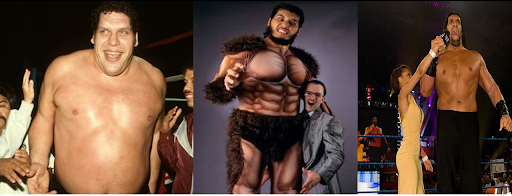

The other mode of presentation is the aggrandized style, which emphasizes that, despite particular physical, mental, or behavioral conditions, the performer is portrayed as an upstanding, high-status individual with talents that are conventionally and socially prestigious. A notable example of this type of “freak” is the image of giants, who were, in reality, individuals with acromegaly, a pituitary disorder, or other endocrine disorders characterized by excessive secretion of growth hormones leading to gigantism. These performers became famous for their appearance and pronounced features, which were, in fact, abnormalities caused by disease pathology.

Medchrome, a website specializing in medical news, lists some of the most famous wrestlers with this condition: André the Giant, a Frenchman who stood at 7 feet 4 inches tall; Giant González, an Argentinian who measured 7 feet 6 inches; and The Great Khali, from India, who is 7 feet 1 inch tall, among others.

Medchrome, a website specializing in medical news, lists some of the most famous wrestlers with this condition: André the Giant, a Frenchman who stood at 7 feet 4 inches tall; Giant González, an Argentinian who measured 7 feet 6 inches; and The Great Khali, from India, who is 7 feet 1 inch tall, among others.

Chemers (2008) considered the contemporary freak show that constructs a narrative of “peculiarity as eminence,” one that employs a postmodern aesthetic and critical position. In this contemporary freak show, we can consider wrestling as well. One of the most popular explanations of why we are attracted to freak shows is because they are discourses not only of deviance but of getting away with deviance (p. 137). According to Fox (2009), this might explain our continued attraction to the freakish elements of reality television, “medical” documentaries on extraordinary bodies, and performers of the excess from the Octomom to Lady Gaga. What is more, his treatment of freakery as a political postmodern performative might benefit from a closer reading of both the performances themselves and their audience reception (Wallin, 2008), particularly in the WWE, where freaks in the ring are portrayed as freaks, sports people, artists, heroes and villains before the eyes of the spectators.

In general, the word freak is a state of mind from the eyes of the spectator, it varies in time, culture and context. Moreover, `freak’ is not a person but a stylized presentation, and we need to separate who people are from how they are presented (Bogdan 1993, p. 93). However, in the spectacle, is not always possible to separate the human being from the thing exhibited. In this sense, the combination wrestling-freak show brings a clear a dichotomy of supernatural terror when the difference is a weapon to win, and natural sympathy when the freakiness is a disadvantage to fight justly.

The world of Wrestling vs The Freak Show: The Spectacle of Excess

In 1972 Rolland Barthes, a French structuralist, wrote the essay The World of Wrestling, which starts with the phrase: “The virtue of all-in wrestling is that it is the spectacle of excess.” This excess can be understood in both spectacles, the wrestling as well as the freak show. As Barthes considers, wrestling contributes to the nature of the great solar spectacles, such as Greek drama and bullfights. The freak show can be included because, as all of them, exacerbate emotions, especially if they are able to merge like wrestling and freak show do. In wrestling, contrary to boxing or judo, is a spectacle intelligible, prepared beforehand, is not developed in front of the viewer but it offers excessive gestures, exploited to the limit of their meaning (p. 16).

Freaks show are, essentially, the exposure of the body exaggerating their characteristics to the excess. The combination of freak-wrestling is even more exaggerated and a greater spectacle. In WWE, we can count midgets, giants, extremely obese people, overstated muscular men, ‘savages’, or even disabled people, among others.

Furthermore, the grandiloquence in both spectacles has similar language and props (masks and disguises) within an exaggeratedly visible explanation of a necessity to be seen and exposed. What is more, wrestling and freak shows could be considered, as Barthes proposed, diacritic writing because in both cases the meaning of the body is fundamental. It is used by wrestlers and sideshows as a primary tool for their work. It constantly helps the reading of the fight by means of gestures, attitudes and mimicry which make the wrestler’s intention utterly obvious. What the public wants is the image of passion, not passion itself (p. 18). The freak show is basically an exposition of the body. In the freak show world, the different body is important, they amplify their uniqueness and how different are from the rest. In other words, the scale of the body is an important factor for wrestlers and freaks.

As an example of the previous, Ron Reis appeared for the first time as the Yeti. He bursts from a block of ice, with his entire body wrapped in bandages, as a mummy. His uniqueness was his height and his lethal weapon was his bear hug attack. Ron Reis was a clumsy wrestler. The bandages hamper his movements, and he seemed uncomfortable. He changed his identity to Super Giant Ninja, but he did not have a successful career as a wrestler. He had appearances in prime-time television thanks to his exaggerated size. His height was his symbol of something attractive or different, which made the intention utterly obvious, as Barthes said. In the end, his time as a professional wrestler finished soon. He pretended to be merciless playing something with a colossal image, but was weak on the ring.

As an example of the previous, Ron Reis appeared for the first time as the Yeti. He bursts from a block of ice, with his entire body wrapped in bandages, as a mummy. His uniqueness was his height and his lethal weapon was his bear hug attack. Ron Reis was a clumsy wrestler. The bandages hamper his movements, and he seemed uncomfortable. He changed his identity to Super Giant Ninja, but he did not have a successful career as a wrestler. He had appearances in prime-time television thanks to his exaggerated size. His height was his symbol of something attractive or different, which made the intention utterly obvious, as Barthes said. In the end, his time as a professional wrestler finished soon. He pretended to be merciless playing something with a colossal image, but was weak on the ring.

However, perhaps the most important exaggeration of the body to the extent to become a freak in WWE is the extreme bodybuilding. Those wrestlers seek to maximize the visible muscularity. Through these practices, bodybuilders defy normative assumptions about human bodies, and that is their particularity: male versus female, natural versus unnatural, normal versus abnormal, illusion and reality (Lindsay, 1996, p. 356).

Scott Steiner was a muscular freak. He was the image of the film “The Circus”, a movie featured by WWE Stars. According to the website strengthfighter.com, he claims to have the biggest arms in wrestling and the largest arms in the world, 26 inches. The same site says that at 49, he is almost crippled due to countless injuries: crushed back vertebrae, foot injury, torn triceps and biceps, a near-fatal throat injury. He is the stereotypical and almost comical professional wrestler; his freak musculature is traduced in power, mak us look powerless to the rest of his opponents.

Scott Steiner was a muscular freak. He was the image of the film “The Circus”, a movie featured by WWE Stars. According to the website strengthfighter.com, he claims to have the biggest arms in wrestling and the largest arms in the world, 26 inches. The same site says that at 49, he is almost crippled due to countless injuries: crushed back vertebrae, foot injury, torn triceps and biceps, a near-fatal throat injury. He is the stereotypical and almost comical professional wrestler; his freak musculature is traduced in power, mak us look powerless to the rest of his opponents.

To emphasize the necessity of visibility, Barthes noted that “the function of the wrestler is not to win; it is to go exactly through the motions that are expected of him.” In this context, we can draw on the definition from the Encyclopedia Britannica, which states that freaks can also be identified by their actions. Thus, wrestlers can be considered freaks due to their performances.

Take, for example, Marty Wright, known as the Boogeyman. His character featured red and black face paint, striking contact lenses, and a jerky, almost surreal movement as he made his way to the ring, complete with a lost expression. He would smash a clock over his head while eating worms, creating a truly intimidating and grotesque presence. His signature move involved chewing a handful of live worms and then vomiting over his opponents, which added to his shock value. However, as Morrell (2015) points out, his inability to perform beyond a basic five-minute match ultimately limited his success.

Take, for example, Marty Wright, known as the Boogeyman. His character featured red and black face paint, striking contact lenses, and a jerky, almost surreal movement as he made his way to the ring, complete with a lost expression. He would smash a clock over his head while eating worms, creating a truly intimidating and grotesque presence. His signature move involved chewing a handful of live worms and then vomiting over his opponents, which added to his shock value. However, as Morrell (2015) points out, his inability to perform beyond a basic five-minute match ultimately limited his success.

In other order of ideas, there exists a complex interplay of contradiction and emphasis in the presentation of freaks in wrestling. As Barthes notes, an essential aspect of wrestling is the immediate consequences of what unfolds during the spectacle; every action elicits a reaction. Typically, the spectacle showcases themes of suffering, defeat, and justice. However, this is merely an image; spectators do not desire the genuine suffering of the contestants, as the spectacle is not sadistic but rather intelligible. Instead, the audience appreciates the perfection of the iconography (p. 20).

The emergence of a true freak, however, complicates this notion of intelligibility. Unlike mere representations, real freaks are actual individuals with bodies that defy conventional proportions. Yet wrestling simultaneously invokes ancient myths of public suffering and humiliation, embodying a profound moral concept of justice. If a freak exploits their differences, the audience is likely to demand retribution. Conversely, if the freak is defeated due to their condition, spectators will seek justice on their behalf.

In this context, Barthes argues that the spectacle engages the audience’s capacity for indignation by presenting the limits of the concept of justice. This confrontation highlights a threshold where even slight transgressions of the rules can unlock the gates to a world devoid of constraints.

We have, for example, one of the most freaking moments of WWE that broke all kind of moral, human and good taste borders. I refer to the history of “Katie Vick”. A woman who supposedly died in a car accident. The wrestler, Triple H, in vengeance of his enemy and ex-boyfriend of the dead woman, went disguised to her funeral and had sex with the corpse inside of the coffin. It seems common sense to consider that as a fake act it was part of the show. However, doubtless, that storyline opened the gates to believe in an abnormal discourse of necrophilia, soulless revenge, an extraordinary example of a freak act.

We have, for example, one of the most freaking moments of WWE that broke all kind of moral, human and good taste borders. I refer to the history of “Katie Vick”. A woman who supposedly died in a car accident. The wrestler, Triple H, in vengeance of his enemy and ex-boyfriend of the dead woman, went disguised to her funeral and had sex with the corpse inside of the coffin. It seems common sense to consider that as a fake act it was part of the show. However, doubtless, that storyline opened the gates to believe in an abnormal discourse of necrophilia, soulless revenge, an extraordinary example of a freak act.

One important concept that connects wrestling and freak shows is the idea of the “bastard,” which describes someone who is unstable and selectively accepts rules only when they serve their interests, transgressing the formal community of attitudes. In matches against freaks, the audience typically supports the more vulnerable contestant, while the bastard manipulates the rules to their advantage. For instance, a bastard may disregard the formal boundaries of the ring by chasing an opponent outside the ropes, only to later invoke those same boundaries to seek protection for their actions.

In contrast, the disability of a freak establishes a consensual boundary that functions as a moral rule. For example, throwing a midget out of the ring, diving onto an opponent who is significantly overweight, or exploiting someone with a mental disability all demonstrate how the abuser violates these moral standards. Such actions render the perpetrator a bastard, undermining the ethical framework that governs the spectacle.

This creates a complex dynamic: the audience may either support the freak for their vulnerability or condemn them for using their differences to gain an advantage. These inconsistencies, along with the treachery and cruelty involved, challenge our understanding of morality and logic, revealing deep contradictions within the spectacle (p. 24).

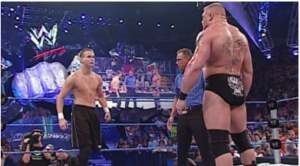

To exemplify this idea of the bastard, we can recall the fight between Brock Lesnar, a stereotype of a ruthless bully, and Zach Gowen, the first one-legged professional wrestler in WWE, whose left leg was removed when he was eight as a result of cancer. In August 2003, this young, small, skinny guy, the weak and hopeless underdog fought against the huge and muscular Lesnar. The only offence that Gowen had was when he dove over Lesnar while he was taunting Gowen’s mother, who was in the front row. Then, Lesnar followed him by clubbing him with the prosthetic leg. Lesnar was disqualified when he clouted the disabled player with a metallic chair. The young wonder bled dramatically in the arms of his mother who jumped the fence to protect him. It was one of the most convincing beatings in the history of WWE. In this match, Lesnar acted as the biggest bastard of its generation. He destroyed a disabled and weak opponent, humiliating both the rival and his mother. He made fun of a body bleeding at his feet and laughed at his mother who was begging him to stop, and, finally, he tried as hard as he could to hurt his only leg. Not only, he also kept beating him when he was on the stretcher and, days later, when Gowen was recovering, Lesnar tied him to a wheelchair and threw him down a flight of stairs.

To exemplify this idea of the bastard, we can recall the fight between Brock Lesnar, a stereotype of a ruthless bully, and Zach Gowen, the first one-legged professional wrestler in WWE, whose left leg was removed when he was eight as a result of cancer. In August 2003, this young, small, skinny guy, the weak and hopeless underdog fought against the huge and muscular Lesnar. The only offence that Gowen had was when he dove over Lesnar while he was taunting Gowen’s mother, who was in the front row. Then, Lesnar followed him by clubbing him with the prosthetic leg. Lesnar was disqualified when he clouted the disabled player with a metallic chair. The young wonder bled dramatically in the arms of his mother who jumped the fence to protect him. It was one of the most convincing beatings in the history of WWE. In this match, Lesnar acted as the biggest bastard of its generation. He destroyed a disabled and weak opponent, humiliating both the rival and his mother. He made fun of a body bleeding at his feet and laughed at his mother who was begging him to stop, and, finally, he tried as hard as he could to hurt his only leg. Not only, he also kept beating him when he was on the stretcher and, days later, when Gowen was recovering, Lesnar tied him to a wheelchair and threw him down a flight of stairs.

Evidently, Lesnar played the role of the evil bastard, Gowen the inoffensive victim, and the spectator the angry judges of this immense immorality. This game of roles finished years later when, according to Hurley (2011) Gowen said “Brock was a real nice guy – he really took care of me. That’s where the magic of pro wrestling is: to make it look like he’s killing me but he’s not really hurting me at all”.

A crucial topic in comparing wrestling and freaks is the notion that, both in the ring and in their moments of ignominy, wrestlers embody a kind of divinity. For brief periods, they become the key that unlocks nature, executing pure gestures that separate Good from Evil and reveal a form of Justice that is finally comprehensible (p. 25). In this light, wrestlers are heroes, and to fulfill this role, they require villains—the dichotomy of good and evil, gods and demons.

When freaks enter the ring, their level of bastardness determines how they are categorized by the audience. The uniqueness of the freak captures the spectator’s attention, and it is up to the audience to uphold the boundaries of the moral code to align with the good side. Should a freak cross these moral lines and behave as a “bastard,” they risk becoming enemies of the collective conscience.

Conclusion

The term “freak” serves as a category for conceptualizing deformity, allowing us to consider those who deviate from our notions of normality. It prompts us to reflect on how society judges these individuals and how we culturally define what is considered normal, shaping our expectations of behavior, appearance, and thought. In essence, the perception of freakiness arises as soon as we encounter someone with extreme differences from our constructed ideas of normality.

Both freak shows and wrestling involve two key elements: the perceivers and the perceived; the performers and the spectators; the audience and the exhibition; the freaks and the normal. These dynamic highlights the interplay between those who need to be seen as different and those who seek to observe that difference in order to affirm their own sense of normalcy.

Wenceslao Amezcua comes from Mexico City and holds degrees in Communication Science, Latin American Studies, and Communications and Public Relations. He has over 14 years of experience as a university lecturer and has taught in high schools in several countries. For the past five years, he has had the true pleasure of teaching at MSVU. He has experience in both mass media and government in the field of communications, and works as a press officer for the Mexican Representation overseas.

Wenceslao Amezcua comes from Mexico City and holds degrees in Communication Science, Latin American Studies, and Communications and Public Relations. He has over 14 years of experience as a university lecturer and has taught in high schools in several countries. For the past five years, he has had the true pleasure of teaching at MSVU. He has experience in both mass media and government in the field of communications, and works as a press officer for the Mexican Representation overseas.

References:

Bogdan, R., (1993). In Defense of Freak Show. Disability, Handicap & Society, 8:1, 91-94, DOI: 10.1080/02674649366780071

Briant, E., Watson, Nick. & Philo, G., (2013). Reporting disability in the age of austerity: the changing face of media representation of disability and disabled people in the United Kingdom and the creation of new ‘folk devils’. Disability & Society, 28:6, 874-889, DOI: 10.1080/09687599.2013.813837

Fox, A. (2009). Review of Staging Stigma. Home. Vol 29, No 4. Retrieved from: http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/1004/1155

Couser, T., (2005). Disability, Life Narrative, and Representation. Modern Language Association, Vol. 120, No. 2, pp. 602-606. Retrieved from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25486192

Goggin, G. & Newell, C. (2000). Crippling paralympics? Media, disability and olympism. Media International Australia incorporating Culture and Policy. No. 97 – November 2000. Pp 71-83. Retrieved from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1329878X0009700110

Hartne, A., (2000). Escaping the ‘Evil Avenger’ and the ‘Supercrip’: Images of Disability in Popular Television. Irish Communications Review, Vol.8, 21-29. Retrieved from: https://arrow.dit.ie/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://scholar.google.ca/&httpsredir=1&article=1011&context=aaschmedart

Hurley, O. (2011). Wrestling’s 101 Strangest Matches.Retrieved from: https://oliverhurley.weebly.com/book-extract-zach-gowen-vs-brock-lesnar.html

Larsen, R., & Haller, B., (2002). The Case of FREAKS, Journal of Popular Film and Television, 29:4, 164-173, DOI: 10.1080/01956050209601022

Lindsay, C. (1996). Bodybuilding: A postmodern freak show. Freakery, Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body. New York University Press. 1996. P. 356-367.

Shakespeare, T., (1994). Cultural Representation of Disabled People: Dustbins for Disavowal? Disability & Society, 9:3, 283-299, DOI: 10.1080/09687599466780341

Scott Steiner Biceps (2012). Retrieved from: http://www.strengthfighter.com/2012/03/scott-steiner-biceps.html

Thoreau, T., (2006). Ouch! An Examination of the Self-Representation of Disabled People on the Internet. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 442–468 a 2006 International Communication Association. DOI:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00021.x

Thomas, C., (2004). How is disability understood? An examination of sociological approaches. Disability & Society, 19:6, 569-583, DOI: 10.1080/0968759042000252506

Wallin, S. (2008) Michael M. Chemers’ Staging Stigma: A Critical Examination of the American Freak Show. Retrieved from:

Whittington-Walsh, F., (2002). From Freaks to Savants: Disability and hegemony from The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939) to Sling Blade (1997). Disability & Society, 17:6, 695-707, DOI: 10.1080/0968759022000010461

Victorian freak shows (n.d.). The British Library. Retrieved from: http://www.bl.uk/learning/cult/bodies/freak/freakshow.html